The word history comes from the root *weid-, "to know, to see".[8] This root is also present in the English words wit, wise, wisdom, vision, and idea, in the Sanskrit word veda,[9]

The word history comes from the root *weid-, "to know, to see".[8] This root is also present in the English words wit, wise, wisdom, vision, and idea, in the Sanskrit word veda,[9]It was still in the Greek sense that Francis Bacon used the term in the late 16th century, when he wrote about "Natural History". For him, historia was "the knowledge of objects determined by space and time", that sort of knowledge provided by memory (while science was provided by reason, and poetry was provided by fantasy).

The word entered the English language in 1390 with the meaning of "relation of incidents, story". In Middle English, the meaning was "story" in general. The restriction to the meaning "record of past events" arises in the late 15th century. In German, French, and most Germanic and Romance languages, the same word is still used to mean both "history" and "story". The adjective historical is attested from 1661, and historic from 1669.[12]

Historian in the sense of a "researcher of history" is attested from 1531. In all European languages, the substantive "history" is still used to mean both "what happened with men", and "the scholarly study of the happened", the latter sense sometimes distinguished with a capital letter, "History", or the word historiography.[11]

Historiography is the history of history, the aspect of history and of semiotics that considers how knowledge of the past, either recent or distant, is obtained and transmitted.[1] Formally, historiography examines the writing of history, the use of historical methods, drawing upon authorship, sources, interpretation, style, bias, and the reader; moreover, historiography also denotes a body of historical work.

Beginning in the nineteenth century, at the ascent of academic history, a corpus of historiography literature developed, including What is History? (1961), by E. H. Carr, and Metahistory (1973), by Hayden White.

text source : http://en.wikipedia.org/

Wedgwood referred to Flaxman's relief model in a letter to his Ornamental Ware partner Thomas Bentley, dated 19 August 1778. Bentley had already interpreted the scene as: '....some honor paid to the genius of Homer'.

Wedgwood referred to Flaxman's relief model in a letter to his Ornamental Ware partner Thomas Bentley, dated 19 August 1778. Bentley had already interpreted the scene as: '....some honor paid to the genius of Homer'.

Eight years later the bas relief was chosen by Josiah Wedgwood as the principal ornament for his most important jasper vase to date, sometimes known as the Pegasus Vase. The first copy of the vase was produced in February 1786. In May of the same year Wedgwood presented a copy of it to the British Museum, saying of it: '...it is the finest and most perfect I have ever made.'

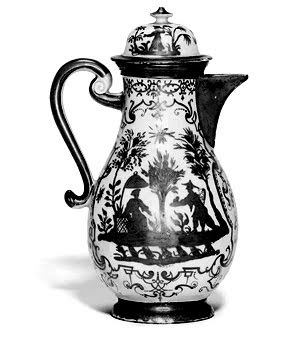

Various examples of the vase exist in a number of collections. The one on display in the Wedgwood museum is made of white jasper, which has received a mid-blue dip, with white bas-relief figures. A superb specimen of the same subject, in a greenish-buff jasper dip, with the Pegasus or winged-horse finial in white, on solid pale blue jasper clouds, is retained by the Castle Museum, Nottingham.

During the 19th century examples of the vase appeared in black basalt. Subsequently smaller-size versions of the vase were issued by Wedgwood in jasper (of varying colours, usually with white bas reliefs) and in more recent times in black with the raised bas-relief ornamentation enhanced by the addition of exquisite gilding. This form of decoration has its source in the latter decades of the 19th century, when exquisite ornamental wares were made in black basalt with the bas-relief figures enhanced by bronzing and gilding.

-----

text and image source : http://www.wedgwoodmuseum.org.uk/

secondary source :http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/