Thursday, February 21, 2013

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Αριστομένης Αγγελόπουλος

Ο Αριστομένης (Μένης) Αγγελόπουλος (Βόλος, 1900 – Παρίσι, 1990) ήταν έλληνας ζωγράφος, ο οποίος έζησε και εργάστηκε για πολλά χρόνια στην Αίγυπτο, το Σουδάν και το Παρίσι.

Ο Αριστομένης (Μένης) Αγγελόπουλος (Βόλος, 1900 – Παρίσι, 1990) ήταν έλληνας ζωγράφος, ο οποίος έζησε και εργάστηκε για πολλά χρόνια στην Αίγυπτο, το Σουδάν και το Παρίσι. Ο Αγγελόπουλος ήταν το ενδέκατο και τελευταίο παιδί μιας βολιώτικης οικογένειας. Λίγο μετά την γέννησή του έχασε την μητέρα του. Έλαβε τα πρώτα μαθήματα ζωγραφικής κοντά στον συμπατριώτη του θαλασσογράφο Γιάννη Πούλακα. Το 1916 έχασε και τον πατέρα του, οπότε αποφάσισε να φύγει για την Μανσούρα της Αιγύπτου, όπου ζούσε ένας του αδελφός. Το 1918 πήγε στην Αλεξάνδρεια για να μαθητεύσει κοντά στον ζωγράφο Δημήτρη Λίτσα. Από το 1924 έως το 1930 ταξίδευσε στο Μόναχο και το Παρίσι, για να γνωρίσει τις σύγχρονες τάσεις της ζωγραφικής σε ακαδημίες, αίθουσες τέχνης και μουσεία.

Το 1930 εγκαταστάθηκε οριστικά στην Αλεξάνδρεια και πρωτοστάτησε στην ίδρυση του πνευματικού κέντρου «L'Atelier», το οποίο εξελίχθηκε σε πόλο έλξης και σημείο αναφοράς για την καλλιτεχνική ζωή της ελληνικής παροικίας και όλης της πόλης. Κατά την διάρκεια του Β΄ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου, γνωρίστηκε με τον Στρατή Τσίρκα και συμμετείχε σε δραστηριότητες για την βοήθεια του ελληνικού λαού, που υπέφερε από τις κακουχίες της Κατοχής. Από το 1955 έως το 1960 διετέλεσε διευθυντής του Τομέα Ζωγραφικής στο Τεχνολογικό Ινστιτούτο του Χαρτούμ στο Σουδάν. Το 1960 εγκατέλειψε το Σουδάν για να εγκατασταθεί οριστικά στο Παρίσι.

Στο Παρίσι, ο Αγγελόπουλος γνώρισε και νυμφεύθηκε την γαλλίδα ζωγράφο Λιλύ Μασσόν (Lily Masson), κόρη του γνωστού υπερρεαλιστή ζωγράφου Αντρέ Μασσόν, 1896–1987). Στην Γαλλία, ήρθε σε επαφή με τα πιο σύγχρονα ρεύματα της εποχής και έτσι εγκατέλειψε για ένα διάστημα, τις ελαιογραφίες με πορτρέτα και τοπία, για να στραφεί προς το πιο αφηρημένο κολλάζ. Λίγα χρόνια αργότερα άφησε και την αφηρημένη τέχνη, για να δημιουργήσει τοπιογραφίες εμπνευσμένες από το παρισινό τοπίο αλλά και την θάλασσα της Μεσογείου. Οι τοπιογραφίες αυτές ξεχωρίζουν για τον φωτογραφικό ρεαλισμό τους και το μοναδικό μεσογειακό τους φως. Σε πολλούς από τους τελευταίους πίνακές του απεικόνισε τον σύγχρονο μικροαστό να αναζητά μόνος του κάποιο διέξοδο στους δρόμους της πόλης.

Τα έργα του Αγγελόπουλου παρουσιάστηκαν σε πολλές ατομικές και ομαδικές εκθέσεις στην Αίγυπτο, το Σουδάν, την Ιταλία, την Γαλλία, το Λουξεμβούργο και την Ελλάδα. Μεταξύ άλλων, το 1951 συμμετείχε στην Μπιενάλε της Βενετίας, την περίοδο 1952–1954 στην Μπιενάλε της Αλεξανδρείας, το 1962 στην έκθεση «Έλληνες ζωγράφοι και γλύπτες του Παρισιού» στο Μουσείο Μοντέρνας Τέχνης της γαλλικής πρωτεύουσας, και το 1983 σε έκθεση στην Εθνική Πινακοθήκη της Ελλάδας. Το 2007, η γενέτειρά του, ο Βόλος, τον τίμησε με αναδρομική έκθεση έργων του.

Από την πρώτη του σύζυγο είχε μία κόρη, την αρχιτεκτόνισσα Ήβη Αγγελοπούλου (1935–2001), και από την τελευταία είχε και μία εγγονή, την επίσης καλλιτέχνιδα Μαριγώ Βλάικου.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Και οταν τα ειχε τακτοποιησει ολα στο κεφαλι του

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

De 'Witte Leeuw'

Kendi uit V.O.C.-schip de 'Witte Leeuw',

Kendi uit V.O.C.-schip de 'Witte Leeuw',Kendi met een vlakke ongeglazuurde bodem, in de vorm van een olifant met op de rug een handvat (nu grotendeels verdwenen). Gedecoreerd in onderglazuur blauw met een kleed met swastika's en een veld met bloemtakken op de rug van de olifant, wolkmotieven rond de stam van het handvat en geluksymbolen op het handvat. Bij de oren, neusgaten en slurf is het glazuur afgebladderd. De scherf is glasachtig wit en kent weinig ingebakken vuil. Het glazuur is blauw getint. De bodem is geglazuurd. Er is geen ovenzand aangetroffen.

source : http://www.rijksmuseum.nl/

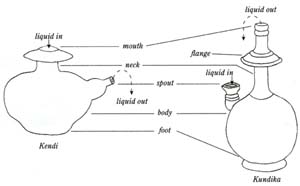

Kendi

Select Bibliography

Adhyatman, Sumarah, 'Kendis, Jars and Other Ceramics: Their Role in Indonesia,1 Paper presented at a conference, Asian Ceramics: Potters, Users, and Collectors,' The Field Museum, Chicago, 7-9 October 1994.

_______ , Kendi, Traditional Drinking Water Container, Jakarta, The Ceramic Society of Indonesia, 1987.

Bhumadhon, Phuthorn, 'Ceramics of the Dvaravati Period in Early Thailand, 6th to 10th Centuries, A.D.' Paper read at the Field Museum's and ACRO's Asian Ceramics Conference, May 1996.

Brown, Roxanna M., The Ceramics of South-East Asia: Their Dating and Identification, 2nd edition, Singapore, Oxford University Press,

1988.

_______ , ed., Guangdong Ceramics from Butuan and other Philippine sites, Manila, the Philippines, Oriental Ceramic Society of the Philippines & Oxford University Press, 1989.

Fisher, Robert E., Buddhist Art and Architecture, London, Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Guy, John, 'Southeast Asian Glazed Ceramics: A Study of Sources,' in New Perspectives on the Art of Ceramics in China, George Kuwayama,ed., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992, pp. 98-114.

Higham, Charles, Early Cultures of Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok, River Books, 2002.

Honda, Hiromu and Noriki Shirnazu, The Beauty of Fired Clay: Ceramics from Burma, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand. Introduction by Dawn F. Rooney, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Indrawooth, Phasook, 'Kendis from Peninsular Thailand, in Muang Boran Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan-Mar 1984.

Kendis: A Guide to the Collections National Museum Singapore, 1984.

Luce, G.H., Old Burma - Early Pagan, Ascona and New York, 1969-70, vol. I.

Nugrahani, D.S., 'Exploring Indonesian Kendi,' TAASA Review, Australia, vol. 5, no. 1, March 1996, pp. 6-7.

Ridho, Abu, White Kendis; Sumarah Adhyatman, Burmese Ceramics Bulletin, Jakarta, The Ceramic Society of Indonesia, May 1985, pp. 42-52.

Rooney, Dawn F., Khmer Ceramics, Singapore, Oxford University Press, 1984.

_________, Folk Pottery in South-East Asia, Singapore, Oxford University Press, 1987.

Sakai, T., The Origin of the Kendi PouringVessel, A Preliminary Note on Its Typological Study,' Journal of East-West Maritime Relations, vol 2,1992 (NB: Waseda University]

Singh, R C. Prasad, 'Spouted Vessels in India,' Potteries in Ancient India, B. P. Sinha, ed, Patna, Department of Ancient Indian History and Archaeology, Patna University, 1969, pp. 118-123.

Soegondho, Santoso, Earthenware Traditions in Indonesia: From Prehistory until the Present, Jakarta, Ceramic Society of Indonesia, n. d..

Spinks, Charles Nelson, The Ceramic Wares of Siam, Bangkok, The Siarn Society, 1965.

Stark, Miriam, 'Pre-Angkor Earthenware: Ceramics from Cambodia's Mekong Delta,' UDAYA Qournal of Khmer Studies), April 2000, pp. 69-89.

Sweetman, John and Nicol Guerin, The Spouted Ewer and its relatives in the Far East, An Oriental Ceramic Society exhibition in the Barlow Gallery. University Library, Falmer, Brighton, University of Sussex, 1983.

Endnotes

i Fisher (1993) Thames and Hudson, pit 95, p. 103.

ii Nugrahani (March 1996) 'Exploring Indonesian kendi', TAASA Review, vol.5, no.l, pp.6-7).

iii Bhumadhon (May 1996).

iv Personal conversations with the Director, October 2001.

v Higham (2002) River Books, p.236.

vi Stark (April 2002), p.79.

vii For examples of Satingpra-type ware, see Guangdong Ceramics, pit 150-4.

viii Guy (1992)

-----

text and image source :http://rooneyarchive.net/articles/kendi/kendi_album/kendi.htm

Thursday, July 1, 2010

the palace kitchens with the tall chimneys

The elongated palace kitchens (Saray Mutfakları) are a prominent feature of the palace. Some of the kitchens were first built in the 15th century at the time when the palace was constructed. They were modeled on the kitchens of the Sultan's palace at Edirne. They were enlarged during the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent but burned down in 1574. The kitchens were remodeled and brought up to date according to the needs of the day by the court architect Mimar Sinan.[31]

Rebuilt to the old plan by Sinan, they form two rows of 20 wide chimneys (added by Sinan), rising like stacks from a ship from domes on octagonal drums. The kitchens are arranged on an internal street stretching between the Second Courtyard and the Sea of Marmara. The entrance to this section is through the three doors in the portico of the Second Courtyard: the Imperial commissariat (lower kitchen) door, imperial kitchen door and the confectionery kitchen door.

The palace kitchens consist of 10 domed buildings: Imperial kitchen, Enderûn (palace school), Harem (women’s quarters), Birûn (outer service section of the palace), kitchens, beveragesconfectionery kitchen, creamery, storerooms and rooms for the cooks. They were the largest kitchens in the Ottoman Empire. The meals for the Sultan, the residents of the Harem, Enderûn and Birûn (the inner and outer services of the palace) were prepared here. Food was prepared for about 4,000 people. The kitchen staff consisted of more than 800 people, rising to 1,000 on religious holidays. As many as 6,000 meals a day could be prepared. Even the serving of food to the sultan was strictly regulated by protocol.[32] kitchen,

The kitchens included dormitories, baths and a mosque for the employees, most of which have disappeared over time.[33]

Apart from exhibiting kitchen utensils, today the buildings contain a silver gifts and utensils collection, as well as large collections of Chinese blue-and-white, white, and celadon porcelain.

Chinese and Far East porcelain was highly valued and was transported by camel caravans over the Silk Road or by sea. The 10,700 pieces of Chinese, Japanese and Turkish porcelain displayed here are rare, precious,[34] and thought to rival that found in China as one of the finest collections in the world.[2] The Chinese porcelain collection ranges from the late Song DynastyYuan Dynasty (1280–1368), through the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) to the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). This museum also contains one of the world's largest collections of 14th-century Longquan celadon. The collection has around 3,000 pieces of Yuan and Ming Dynasty celadons.[35] Those celadon were valued by the Sultan and the Queen Mother because it was supposed to change colour if the food or drink it carried was poisoned.[36] The Japanese collection is mainly Imari porcelain, dating from the 17th to the 19th century. Further parts of the collection include white porcelain from the beginning of the 15th century and "imitation" Blue-and-White and Imari porcelain from Vietnam, Thailand and Persia.[37]

.jpg)