Saturday, November 20, 2010

Αριστομένης Αγγελόπουλος

Ο Αριστομένης (Μένης) Αγγελόπουλος (Βόλος, 1900 – Παρίσι, 1990) ήταν έλληνας ζωγράφος, ο οποίος έζησε και εργάστηκε για πολλά χρόνια στην Αίγυπτο, το Σουδάν και το Παρίσι.

Ο Αριστομένης (Μένης) Αγγελόπουλος (Βόλος, 1900 – Παρίσι, 1990) ήταν έλληνας ζωγράφος, ο οποίος έζησε και εργάστηκε για πολλά χρόνια στην Αίγυπτο, το Σουδάν και το Παρίσι. Ο Αγγελόπουλος ήταν το ενδέκατο και τελευταίο παιδί μιας βολιώτικης οικογένειας. Λίγο μετά την γέννησή του έχασε την μητέρα του. Έλαβε τα πρώτα μαθήματα ζωγραφικής κοντά στον συμπατριώτη του θαλασσογράφο Γιάννη Πούλακα. Το 1916 έχασε και τον πατέρα του, οπότε αποφάσισε να φύγει για την Μανσούρα της Αιγύπτου, όπου ζούσε ένας του αδελφός. Το 1918 πήγε στην Αλεξάνδρεια για να μαθητεύσει κοντά στον ζωγράφο Δημήτρη Λίτσα. Από το 1924 έως το 1930 ταξίδευσε στο Μόναχο και το Παρίσι, για να γνωρίσει τις σύγχρονες τάσεις της ζωγραφικής σε ακαδημίες, αίθουσες τέχνης και μουσεία.

Το 1930 εγκαταστάθηκε οριστικά στην Αλεξάνδρεια και πρωτοστάτησε στην ίδρυση του πνευματικού κέντρου «L'Atelier», το οποίο εξελίχθηκε σε πόλο έλξης και σημείο αναφοράς για την καλλιτεχνική ζωή της ελληνικής παροικίας και όλης της πόλης. Κατά την διάρκεια του Β΄ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου, γνωρίστηκε με τον Στρατή Τσίρκα και συμμετείχε σε δραστηριότητες για την βοήθεια του ελληνικού λαού, που υπέφερε από τις κακουχίες της Κατοχής. Από το 1955 έως το 1960 διετέλεσε διευθυντής του Τομέα Ζωγραφικής στο Τεχνολογικό Ινστιτούτο του Χαρτούμ στο Σουδάν. Το 1960 εγκατέλειψε το Σουδάν για να εγκατασταθεί οριστικά στο Παρίσι.

Στο Παρίσι, ο Αγγελόπουλος γνώρισε και νυμφεύθηκε την γαλλίδα ζωγράφο Λιλύ Μασσόν (Lily Masson), κόρη του γνωστού υπερρεαλιστή ζωγράφου Αντρέ Μασσόν, 1896–1987). Στην Γαλλία, ήρθε σε επαφή με τα πιο σύγχρονα ρεύματα της εποχής και έτσι εγκατέλειψε για ένα διάστημα, τις ελαιογραφίες με πορτρέτα και τοπία, για να στραφεί προς το πιο αφηρημένο κολλάζ. Λίγα χρόνια αργότερα άφησε και την αφηρημένη τέχνη, για να δημιουργήσει τοπιογραφίες εμπνευσμένες από το παρισινό τοπίο αλλά και την θάλασσα της Μεσογείου. Οι τοπιογραφίες αυτές ξεχωρίζουν για τον φωτογραφικό ρεαλισμό τους και το μοναδικό μεσογειακό τους φως. Σε πολλούς από τους τελευταίους πίνακές του απεικόνισε τον σύγχρονο μικροαστό να αναζητά μόνος του κάποιο διέξοδο στους δρόμους της πόλης.

Τα έργα του Αγγελόπουλου παρουσιάστηκαν σε πολλές ατομικές και ομαδικές εκθέσεις στην Αίγυπτο, το Σουδάν, την Ιταλία, την Γαλλία, το Λουξεμβούργο και την Ελλάδα. Μεταξύ άλλων, το 1951 συμμετείχε στην Μπιενάλε της Βενετίας, την περίοδο 1952–1954 στην Μπιενάλε της Αλεξανδρείας, το 1962 στην έκθεση «Έλληνες ζωγράφοι και γλύπτες του Παρισιού» στο Μουσείο Μοντέρνας Τέχνης της γαλλικής πρωτεύουσας, και το 1983 σε έκθεση στην Εθνική Πινακοθήκη της Ελλάδας. Το 2007, η γενέτειρά του, ο Βόλος, τον τίμησε με αναδρομική έκθεση έργων του.

Από την πρώτη του σύζυγο είχε μία κόρη, την αρχιτεκτόνισσα Ήβη Αγγελοπούλου (1935–2001), και από την τελευταία είχε και μία εγγονή, την επίσης καλλιτέχνιδα Μαριγώ Βλάικου.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Και οταν τα ειχε τακτοποιησει ολα στο κεφαλι του

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

De 'Witte Leeuw'

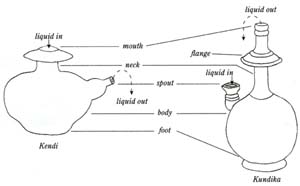

Kendi uit V.O.C.-schip de 'Witte Leeuw',

Kendi uit V.O.C.-schip de 'Witte Leeuw',Kendi met een vlakke ongeglazuurde bodem, in de vorm van een olifant met op de rug een handvat (nu grotendeels verdwenen). Gedecoreerd in onderglazuur blauw met een kleed met swastika's en een veld met bloemtakken op de rug van de olifant, wolkmotieven rond de stam van het handvat en geluksymbolen op het handvat. Bij de oren, neusgaten en slurf is het glazuur afgebladderd. De scherf is glasachtig wit en kent weinig ingebakken vuil. Het glazuur is blauw getint. De bodem is geglazuurd. Er is geen ovenzand aangetroffen.

source : http://www.rijksmuseum.nl/

Kendi

Select Bibliography

Adhyatman, Sumarah, 'Kendis, Jars and Other Ceramics: Their Role in Indonesia,1 Paper presented at a conference, Asian Ceramics: Potters, Users, and Collectors,' The Field Museum, Chicago, 7-9 October 1994.

_______ , Kendi, Traditional Drinking Water Container, Jakarta, The Ceramic Society of Indonesia, 1987.

Bhumadhon, Phuthorn, 'Ceramics of the Dvaravati Period in Early Thailand, 6th to 10th Centuries, A.D.' Paper read at the Field Museum's and ACRO's Asian Ceramics Conference, May 1996.

Brown, Roxanna M., The Ceramics of South-East Asia: Their Dating and Identification, 2nd edition, Singapore, Oxford University Press,

1988.

_______ , ed., Guangdong Ceramics from Butuan and other Philippine sites, Manila, the Philippines, Oriental Ceramic Society of the Philippines & Oxford University Press, 1989.

Fisher, Robert E., Buddhist Art and Architecture, London, Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Guy, John, 'Southeast Asian Glazed Ceramics: A Study of Sources,' in New Perspectives on the Art of Ceramics in China, George Kuwayama,ed., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992, pp. 98-114.

Higham, Charles, Early Cultures of Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok, River Books, 2002.

Honda, Hiromu and Noriki Shirnazu, The Beauty of Fired Clay: Ceramics from Burma, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand. Introduction by Dawn F. Rooney, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Indrawooth, Phasook, 'Kendis from Peninsular Thailand, in Muang Boran Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan-Mar 1984.

Kendis: A Guide to the Collections National Museum Singapore, 1984.

Luce, G.H., Old Burma - Early Pagan, Ascona and New York, 1969-70, vol. I.

Nugrahani, D.S., 'Exploring Indonesian Kendi,' TAASA Review, Australia, vol. 5, no. 1, March 1996, pp. 6-7.

Ridho, Abu, White Kendis; Sumarah Adhyatman, Burmese Ceramics Bulletin, Jakarta, The Ceramic Society of Indonesia, May 1985, pp. 42-52.

Rooney, Dawn F., Khmer Ceramics, Singapore, Oxford University Press, 1984.

_________, Folk Pottery in South-East Asia, Singapore, Oxford University Press, 1987.

Sakai, T., The Origin of the Kendi PouringVessel, A Preliminary Note on Its Typological Study,' Journal of East-West Maritime Relations, vol 2,1992 (NB: Waseda University]

Singh, R C. Prasad, 'Spouted Vessels in India,' Potteries in Ancient India, B. P. Sinha, ed, Patna, Department of Ancient Indian History and Archaeology, Patna University, 1969, pp. 118-123.

Soegondho, Santoso, Earthenware Traditions in Indonesia: From Prehistory until the Present, Jakarta, Ceramic Society of Indonesia, n. d..

Spinks, Charles Nelson, The Ceramic Wares of Siam, Bangkok, The Siarn Society, 1965.

Stark, Miriam, 'Pre-Angkor Earthenware: Ceramics from Cambodia's Mekong Delta,' UDAYA Qournal of Khmer Studies), April 2000, pp. 69-89.

Sweetman, John and Nicol Guerin, The Spouted Ewer and its relatives in the Far East, An Oriental Ceramic Society exhibition in the Barlow Gallery. University Library, Falmer, Brighton, University of Sussex, 1983.

Endnotes

i Fisher (1993) Thames and Hudson, pit 95, p. 103.

ii Nugrahani (March 1996) 'Exploring Indonesian kendi', TAASA Review, vol.5, no.l, pp.6-7).

iii Bhumadhon (May 1996).

iv Personal conversations with the Director, October 2001.

v Higham (2002) River Books, p.236.

vi Stark (April 2002), p.79.

vii For examples of Satingpra-type ware, see Guangdong Ceramics, pit 150-4.

viii Guy (1992)

-----

text and image source :http://rooneyarchive.net/articles/kendi/kendi_album/kendi.htm

Thursday, July 1, 2010

the palace kitchens with the tall chimneys

The elongated palace kitchens (Saray Mutfakları) are a prominent feature of the palace. Some of the kitchens were first built in the 15th century at the time when the palace was constructed. They were modeled on the kitchens of the Sultan's palace at Edirne. They were enlarged during the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent but burned down in 1574. The kitchens were remodeled and brought up to date according to the needs of the day by the court architect Mimar Sinan.[31]

Rebuilt to the old plan by Sinan, they form two rows of 20 wide chimneys (added by Sinan), rising like stacks from a ship from domes on octagonal drums. The kitchens are arranged on an internal street stretching between the Second Courtyard and the Sea of Marmara. The entrance to this section is through the three doors in the portico of the Second Courtyard: the Imperial commissariat (lower kitchen) door, imperial kitchen door and the confectionery kitchen door.

The palace kitchens consist of 10 domed buildings: Imperial kitchen, Enderûn (palace school), Harem (women’s quarters), Birûn (outer service section of the palace), kitchens, beveragesconfectionery kitchen, creamery, storerooms and rooms for the cooks. They were the largest kitchens in the Ottoman Empire. The meals for the Sultan, the residents of the Harem, Enderûn and Birûn (the inner and outer services of the palace) were prepared here. Food was prepared for about 4,000 people. The kitchen staff consisted of more than 800 people, rising to 1,000 on religious holidays. As many as 6,000 meals a day could be prepared. Even the serving of food to the sultan was strictly regulated by protocol.[32] kitchen,

The kitchens included dormitories, baths and a mosque for the employees, most of which have disappeared over time.[33]

Apart from exhibiting kitchen utensils, today the buildings contain a silver gifts and utensils collection, as well as large collections of Chinese blue-and-white, white, and celadon porcelain.

Chinese and Far East porcelain was highly valued and was transported by camel caravans over the Silk Road or by sea. The 10,700 pieces of Chinese, Japanese and Turkish porcelain displayed here are rare, precious,[34] and thought to rival that found in China as one of the finest collections in the world.[2] The Chinese porcelain collection ranges from the late Song DynastyYuan Dynasty (1280–1368), through the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) to the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). This museum also contains one of the world's largest collections of 14th-century Longquan celadon. The collection has around 3,000 pieces of Yuan and Ming Dynasty celadons.[35] Those celadon were valued by the Sultan and the Queen Mother because it was supposed to change colour if the food or drink it carried was poisoned.[36] The Japanese collection is mainly Imari porcelain, dating from the 17th to the 19th century. Further parts of the collection include white porcelain from the beginning of the 15th century and "imitation" Blue-and-White and Imari porcelain from Vietnam, Thailand and Persia.[37]

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

What are Artists' Books?

What are Artists' Books? according to V&A

Definitions

Artists' books is the broad term used to describe books, unique or multiple, that have been made or conceived by artists. There are fine artists who make books and book artists who produce work exclusively in that medium, as well as illustrators, typographers, writers, poets, book binders, printers and many others who work collaboratively or alone to produce artists' books. Many artists' books are self-published, or are produced by small presses or by artists' groups or collectives, usually in limited editions. There are many terms used to describe artists' books. Some of the most frequently used terms are book art or bookworks (these terms implying an affinity with the traditional structure of the book) while those that are sculptural objects that allude to the form of the book are commonly referred to as book objects. All of the terms that have been mentioned here are used in the Visual Database of Artists' Books. The database also includes other types of works produced by artists in the book format such as concrete poetry, a genre of visual poetry where the meaning is derived from the spatial, pictorial and typographic characteristics of the work, as well as from the sense of the words.

Origins & Development

Contemporary artists' books are noteworthy for the multiplicity of forms in which they are found. It is perhaps for this reason that historians of the genre frequently identify a myriad of precursors and influences. Artists and their associations with books date back to the era of manuscript production. Many artists through the centuries have been concerned with books as an artistic enterprise, notably William Blake at the end of the 18th century and William Morris at the Kelmscott Press from the 1890s. Avant-garde artists throughout the 20th century have also produced many books as part of their artistic endeavours such as periodicals, pamphlets and manifestos. This list merely scratches the surface of potential influences and precursors to contemporary artists' books which are drawn out more fully in numerous works in the bibliography section of this site.

It is however the livre d'artiste, also known as the livre de peintre, that is generally considered to be a key precursor to the genre of artists' books. Originating in France around the turn of the 20th century, the livre d'artiste is a form of illustrated book. The essential feature that distinguishes it from its predecessors is that each illustration is executed by the artist directly onto the medium from which it is printed, rather than being transferred from an artist's design by a technician. An early exponent of the livre d'artiste was the dealer Ambroise Vollard who commissioned Pierre Bonnard to illustrate with lithographs a collection of poems by Paul Verlaine, Parallèlement, published in Paris in 1900 (NAL pressmark: Safe 1.A.1). The works produced were essentially deluxe, limited editions, produced on high quality paper using specialized printers. They were generally left unbound so that they could be dismantled for display and also so that bespoke bindings could be commissioned if desired. Vollard produced numerous works in association with a number of artists, matching them up with texts to illustrate. Various other publishers followed suit, collaborating with artists of their own association. The National Art Library holds a number of livres d'artistes which are described in the exhibition catalogue: From Manet to Hockney: modern artists' illustrated books , edited by Carol Hogben and Rowan Watson, London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985. (NAL pressmark: CTR REF)

It is generally accepted that the conceptual work of Dieter Roth and Ed Ruscha in the 1950s and 1960s mark the foundations of the genre of artists' books. In 1962 Ed Ruscha published the first edition of Twenty-six gasoline stations (NAL pressmark: SA.91.0042) which comprised 26 deadpan photographs of gasoline stations along Route 66 from Los Angeles to Oklahoma City. This book was not intended as a means for the reproduction of pre-existing photographs, but rather it was deliberately designed as a primary object in its own right; it was in fact an artwork. The essential characteristics of the book format, such as ideas of seriality and sequence provided by the turning of pages, were an inherent aspect of the work and as such it is credited as a seminal example in the advent of a new genre that has come to be defined as artists' books. Ruscha produced a series of bookworks in a similar vein. A further characteristic of this series was that they were published in unlimited editions, had a wide distribution and were inexpensive to buy in a deliberate attempt to bring art to a wider audience. A contemporaneous pioneer of artists' books was Dieter Roth. Roth's distinctive contribution to the emergent genre was his examination, through his bookworks, of the formal qualities of books themselves. These formal qualities such as flat pages, bound into fixed sequences were deconstructed and investigated, for instance in 2 Bilderbücher (1957) (NAL pressmark: X920000) which comprised 2 picture books of geometric shapes, with die-cut holes cut into each page to allow glimpses of patterns from the pages beneath. Structural investigations such as these became the subject matter of the book itself. Subsequent works such as Daily Mirror (1961) involved the use of found materials manipulated to a particular purpose, a technique much used by later book artists.

Artists' Books Reading List

The following is an introductory reading list on artists' books (expert from the V&A museum website)

- Bury, Stephen. Artists' Books: the Book as a Work of Art, 1963-1995. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1995. NAL pressmark: AB.95.0014

- Castleman, Riva. A Century of Artists Books. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1994. NAL pressmark: AB.94.0020

- Chapon, François. Le Peintre et le Livre: l'Age d'Or du Livre Illustré en France 1870-1970. Paris: Flammarion, 1987.

NAL pressmark: 507.C.172

- Courtney, Cathy. Speaking of Book Art: Interviews with British and American Book Artists. Los Altos Hills: Anderson-Lovelace, 1999. NAL pressmark: AB.99.0001

- Drucker, Johanna. The Century of Artists Books. New York: Granary Books, 1995.

NAL pressmark: 602.AC.0054

- Hogben, Carol and Rowan Watson, eds. From Manet to Hockney: Modern Artists' Illustrated Books. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985.

NAL pressmark: 603.AA.0251

- Hubert, Renée Riese and Judd D. Hubert. The Cutting Edge of Reading: Artists' Books. New York: Granary Books, 1999. NAL pressmark: AB.99.0007

- Johnson, Robert Flynn. Artists Books in the Modern Era 1870-2000: the Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books. London : Thames & Hudson, 2002.

NAL pressmark: AB.2001.0002

- The Journal of Artists' Books: JAB. New York: Interplanetary Productions, 1994-

NAL pressmark: PP.115.A

- Klima, Stefan. Artists Books: a Critical Survey of the Literature . New York: Granary Books, 1998. NAL pressmark: AB.98.0013

- Moeglin-Delcroix, Anne. Esthétique du Livre d'Artiste: 1960/1980. Paris: Jean-Michel Place; Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1997. NAL pressmark: AB.97.0003

- Peixoto, Tanya et al., ed. Artist's Book Yearbook. Stanmore: Magpie Press, 1995-

NAL pressmark: individually pressmarked for each year held

- Lyons, Joan, ed. Artists' books: a Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. New York: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1985. NAL pressmark: AB.85.0001

- Turner, Silvie and Ian Tyson, eds. British Artists' Books, 1970-1983: an Exhibition . London: Lund Humphries, 1984. NAL pressmark: AB.84.0002

Text and images source : http://www.vam.ac.uk/index.html

Types of books according to their contents

A common separation by content are fiction and non-fictional books. By no means are books limited to this classification, but it is a separation that can be found in most collections, libraries, and bookstores.

Fiction

Many of the books published today are fictitious stories. They are in-part or completely untrue or fantasy. Historically, paper production was considered too expensive to be used for entertainment. An increase in global literacy and print technology led to the increased publication of books for the purpose of entertainment, and allegorical social commentary. Most fiction is additionally categorized by genre.

The novel is the most common form of fictional book. Novels are stories that typically feature a plot, setting, themes and characters. Stories and narrative are not restricted to any topic; a novel can be whimsical, serious or controversial. The novel has had a tremendous impact on entertainment and publishing markets.[22] A novella is a term sometimes used for fictional prose typically between 17,500 and 40,000 words, and a novelette between 7,500 and 17,500. A Short story may be any length up to 10,000 words, but these word lengths are not universally established.

Comic books or graphic novels are books in which the story is not told, but illustrated.

Non-fiction

In a library, a reference book is a general type of non-fiction book which provides information as opposed to telling a story, essay, commentary, or otherwise supporting a point of view. An almanac is a very general reference book, usually one-volume, with lists of data and information on many topics. An encyclopedia is a book or set of books designed to have more in-depth articles on many topics. A book listing words, their etymology, meanings, and other information is called a dictionary. A book which is a collection of maps is an atlas. A more specific reference book with tables or lists of data and information about a certain topic, often intended for professional use, is often called a handbook. Books which try to list references and abstracts in a certain broad area may be called an index, such as Engineering Index, or abstracts such as chemical abstracts and biological abstracts.

Books with technical information on how to do something or how to use some equipment are called instruction manuals. Other popular how-to books include cookbooks and home improvement books.

Students typically store and carry textbooks and schoolbooks for study purposes. Elementary school pupils often use workbooks, which are published with spaces or blanks to be filled by them for study or homework. In US higher education, it is common for a student to take an exam using a blue book.

There is a large set of books that are made only to write private ideas, notes, and accounts. These books are rarely published and are typically destroyed or remain private. Notebooks are blank papers to be written in by the user. Students and writers commonly use them for taking notes. Scientists and other researchers use lab notebooks to record their spork. They often feature spiral coil bindings at the edge so that pages may easily be torn out.

Address books, phone books, and calendar/appointment books are commonly used on a daily basis for recording appointments, meetings and personal contact information.

Books for recording periodic entries by the user, such as daily information about a journey, are called logbooks or simply logs. A similar book for writing the owner's daily private personal events, information, and ideas is called a diary or personal journal.

Businesses use accounting books such as journals and ledgers to record financial data in a practice called bookkeeping.

Other types

There are several other types of books which are not commonly found under this system. Albums are books for holding a group of items belonging to a particular theme, such as a set of photographs, card collections, and memorabilia. One common example is stamp albums, which are used by many hobbyists to protect and organize their collections of postage stamps. Such albums are often made using removable plastic pages held inside in a ringed binder or other similar smolder.

Hymnals are books with collections of musical hymns that can typically be found in churches. Prayerbooks or missals are books that contain written prayers and are commonly carried by monks, nuns, and other devoted followers or clergy.

text and images : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

Saturday, January 9, 2010

Proposal for the exhibition the Power of Copy, Apostolos Ntelakos

1.

The Xiamen University in China organises a contemporary design exhibition around the concept of copy. The exhibition, named the power of copy is going to take place in Xuzhou, in May 2010.

2.

Looking back at the history of the Applied Arts (in relationship of course to China) one cannot avoid but come across the chinoiserie(1). A French term, meaning "Chinese-esque", normally used to characterize a European style in art that flourished in the late 17th and 18th…(2)

… a complex phenomenon that has taken many different shapes and produced a wide variety of objects and styling – from splendid works of art and excellent examples of craftsmanship to mass-produced pieces of rubbish(3).

3.

In my work historical facts are playing more and more an important role. I am interested in what has happened, how things looked like and what a re-construction of such facts could mean today.

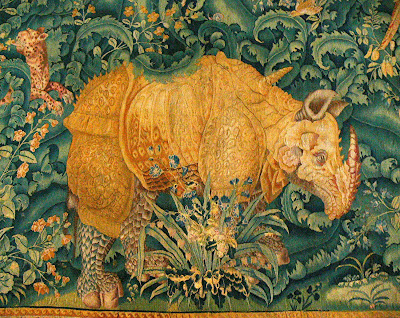

This exhibition in Xiamen seemed like a perfect opportunity to present work: Thinking of China my first association has been vases. More specifically porcelain vases, the ones that Europeans started importing already since the fifteenth and sixteenth century(4).

Going through digitalized archives, books and catalogues I made photocopies / prints of images that attracted me. Taking these prints as reference I tried to re-construct the shape of the vases (executed in stoneware covered with a slip of porcelain). By zooming-in at the images those vases carried, I took parts of them (the images) and tried to re-construct them by means of on-glaze colours (lusters).

4.

How accurate or authentic are images that we artists and designers use? Where lies the difference between functional objects and sculptures of them? Where is the line between a copy, an interpretation, or a reconstruction? Is copying per se passive? Copying occurred for centuries between east and west; European craftsmen attempted to imitate the styles and techniques of decorative art imported from the Middle and Far East. Those craftsmen not only copied designs from imported objects, but also adapted these objects in creative ways(5). And if distortions / mutations occured in this process of copy, were they pure accidents or were they projections of the one who was copying? And what do these distortions tell us about the copyist?

5.

Jean-Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702–1789), Still Life Tea Set, 1783

Jean-Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702–1789), Still Life Tea Set, 1783-----

(1) chinoiserie |ʃɪnˌwɑːzəri|, noun ( pl. -ries)the imitation or evocation of Chinese motifs and techniques in Western art, furniture, and architecture, esp. in the 18th century.

ORIGIN late 19th cent.: from French, from chinois ‘Chinese.’

(2) Arie Pos, (2008) “Het paviljoen van porselein. Nederlandse literaire chinoiserie en het westerse beeld van China (1250-2007)”, proefschrift (Leiden 2008), https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/simple-search?query=Chinoiserie&submit=Go

(3) idem

(4)Munger, Jeffrey, and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen. "East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ewpor/hd_ewpor.htm (October 2003)

(5) Imagining the Orient, October 5, 2004–April 3, 2005, http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/orient/